S1968 – An act relative to certain easements

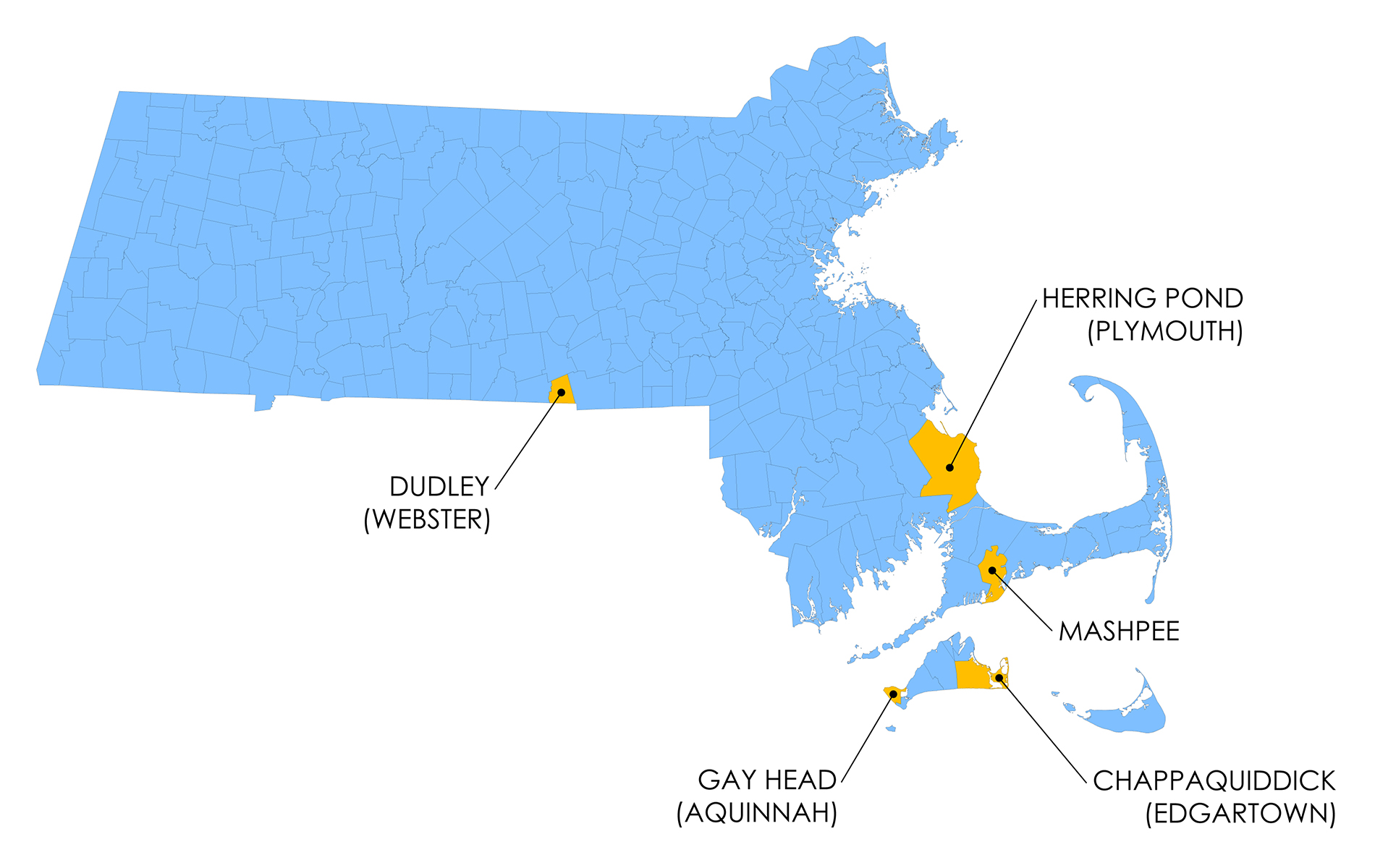

PREAMBLE. By Chapter 463 of the Acts of 1869, the Legislature enfranchised all Native American Indians and declared that they were citizens of the Commonwealth, entitled to all the rights, privileges and duties of other citizens. The Act also affirmed that lands previously set off to any Indian were to become the property of such person and his heirs in fee simple. Thereafter, various acts were adopted for the disposition of common lands at Chappaquiddick, Dudley, Gay Head, Herring Pond and Mashpee. The previously set off lands and the lands divided from the common lands were intended to have the full rights and benefits of property ownership, including the right to reasonable residential use and access.

SECTION 1. Notwithstanding any general or special law to the contrary, lots created for the Native American Indians at Chappaquiddick, Dudley, Gay Head, Herring Pond or Mashpee, and the lots created from the partition of common lands in those former Indian districts, shall be deemed to have been granted in fee simple absolute with no restraint on alienation. If express easements do not exist for such lots, the superior court shall have jurisdiction to establish forty-foot wide easements to a public way over public lands, including land held by any land bank, for vehicular access and underground utilities to such lots. If public lands are not available to provide an express easement to any such lot, new forty-foot wide easements shall be created to the nearest public way by the superior court, with the court establishing all the necessary parties required for an equitable resolution. Such easements shall be considered ways that were in existence when the subdivision control law became effective in the city or town in which the land lies, providing sufficient frontage, width, suitable grades and adequate construction to support the needs of vehicular traffic in relation to the residential use of the land, for adequate public safety and for the installation of underground utilities to serve such land and the buildings erected or to be erected thereon. The frontage of the easements shall be of such distance as is required by zoning or other ordinance or by-law, to allow for residential dwellings on such lots.

The statute of Chief Massasoit in Plymouth. Massasoit was the sachem of the Wampanoag people of southeastern Massachusetts in the first half of the 17th century.

BACKGROUND INFORMATION FOR MA S1968

During the 19th century, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts (who claimed the underlying fee title of all public lands in the state since the Treaty of Paris in 1783) took deliberate steps to recognize and protect Native American lands and the rights of Indians to claim their lands.

Under the provisions of Chapter 266 of the Acts of 1859, the Massachusetts Legislature commissioned John Milton Earle to report on the condition of each remaining Native American Tribe in the state. See Report to the Governor and Council, concerning the Indians of the Commonwealth, under the Act of April 6, 1859, by John Milton Earle, Commissioner. The five most significant remaining Tribes described by Earle were at Chappaquiddick, Dudley, Gay Head, Herring Pond and Mashpee. The Commonwealth then appointed commissioners to identify Indians who possessed and occupied their lands (referred to as “lands held in severalty”.) Deeds were granted, providing absolute title to individual Indians and the power to alienate their land. Lands that were not claimed by individual Indians in the five districts were set aside and identified as general fields or commons, with the title remaining with the Commonwealth.

The Legislature then enfranchised all Indians and declared that they were “hereby made and declared to be citizens of the Commonwealth, and entitled to all the rights, privileges and immunities, and subject to all the duties and liabilities to which citizens of this Commonwealth are entitled or subject.” Chapter 463 of the Acts of 1869.

The purpose of Massachusetts S1968 is to ensure that descendants of the original grantees in the five Indian districts, and their successors in title, continue to enjoy the right to access and use their property as the Legislature intended.

The Legislative history and case law from each of the major 19th century Indian districts can be explored by clicking on a district below: